Kirschner, P. A., & Hendrick, C. (2020). How Learning Happens: Seminal Works in Educational Psychology and What They Mean in Practice. Routledge.

Chapter 21 Learning techniques that really work

I have read several books and lots of articles on this ‘strategies that work’ area, mainly in search of material for a Delta Module Two input session to debunk the VAK / multiple intelligences happy clappy stuff about learning styles. Kirschener et al recommend a meta study by Dunlosky that investigates ten popular techniques students and teachers use for learning to assess whether they are actually effective.

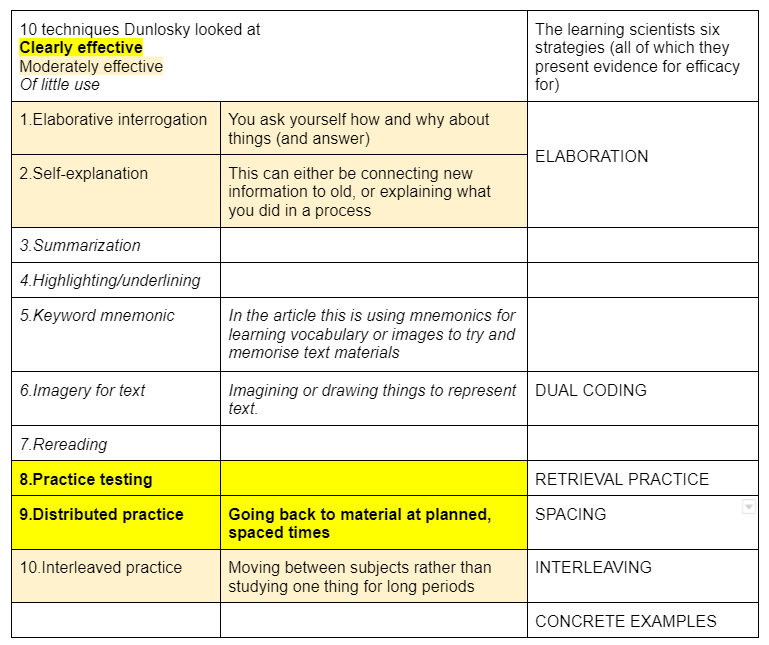

Dunlosky sifts through studies that might provide evidence for the efficacy or otherwise of the techniques. Their conclusion is that (8) practice testing and (9) distributed practice have clear support of their efficiency, (1) elaborative interrogation, (2) self-explanation and (10) interleaved practice seem to be moderately effective and (3) summarization, (4) highlighting, (5) mnemonics, (6) using imagery and (7) re reading seem to be of little use. Kirschener and Hendrick report all this fairly directly.

I was surprised that (3) summarization was said to be of little use as surely that forces you to process the material and realise if you have understood it or not, but it turns out the caveats are because (a) what can be said to be a summary varies so widely and (b) you have to be able to write a good summary (if you can then it is effective) and many people can’t. I knew (4) highlighting and (7) rereading were ineffective. Both make you think you know and understand things when actually you are likely just recognising them which may not involve either knowing or understanding. I can only see (5) mnemonics working for a very limited range of things, so it makes sense that it comes up as ineffective.

When you compare this to the six strategies the learning scientists present (in reading they seem to encapsulate what I have read on research based effective techniques), they have all the strategies Dunlosky found effective, but they also have using concrete examples (especially examples that cross domains so underlying concepts are made clear). Kirschner mentions this a lot in other chapters though. The one point where Dunlosky and the learning scientists seem to differ is on imagery / dual coding and even there maybe they are in fact talking about different things. Dunlosky reports on studies where students were asked to create or draw mental images as they listened or read and found some positive results but much that was so mixed with minor variations from study to study that it is hard to say unequivocally if imagery is effective or not. The learning scientists describe a wider remit where transforming information into flow diagrams or charts are also included as ‘images’. They also say you should then recreate the main ideas from the images and toggle back and forth between the two. This sounds like considerably more processing, so perhaps that is what makes the difference.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive And Educational Psychology. Psychological Science In The Public Interest, 14, 4–58.